Glasgow's harbour on the River Clyde was an artery of the commercial revolution. Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

As effectively as being Scotland’s largest metropolis, Glasgow was its industrial coronary heart. Central to the civic story, is the River Clyde, famed as a worldwide shipbuilding hub within the twentieth century. But the Clyde, together with an considerable provide of coal, additionally made Glasgow the best location for the textile trade. In the 1820s, spinning mills, weaving mills, dye homes and garment factories sprang up, dominated the city panorama.

Access to the general public sphere and the skilled world had been the prerogative of males within the 1800s. But the textile trade offered a possibility for girls. From the introduction of automated looms and stitching machines, equipment turned much less bodily demanding to function. That gave girls a bonus, and in Glasgow, they started to step out of their houses to assert a spot on the manufacturing unit flooring.

Men remained dominant in managerial positions. Women have been paid on common between one third and one half of what males earned. In response, Glasgow’s pioneering feminine staff started a battle to profoundly change the circumstances for girls dwelling and dealing world wide. It would take a long time, however they ultimately enabled their fellow girls to achieve visibility and better rights, each within the office and all through society.

Emily Patmore, 1851, by John Everett Millais.

Wikiart

I’ve been sifting by analysis and paperwork as a part of my doctoral research and so they reveal extra in regards to the attitudes and obstacles these groundbreaking girls confronted. Such perception into these lives makes their achievements all of the extra exceptional.

As Glasgow’s textile trade expanded within the 1800s, girls represented a rising share of the workforce. As the municipal archives present, town had 403,120 inhabitants in 1861, 58% of whom have been girls. Of these, 65% have been working girls, nearly all of whom have been employed by the textile industries. They got here to be seen as a plentiful provide of low cost labour and have been, as historian Judith Walkowitz has stated, the “image of commercial exploitation”.

Factory work and sexuality

The affiliation of girls and machines was in itself controversial and prompted a fierce debate. As girls shifted into manufacturing unit work, they have been compelled to make use of looms and different machines for as much as 12 hours a day, with repetitive gestures. They turned, within the eyes of the male supervisors and foremen, “machine girls”, bewitched and disembodied. And when femininity was related to this strangeness, it elicited concern in males. The males got here to consider themselves as inquisitors and the machine turned the pillory, with girls condemned to subordination.

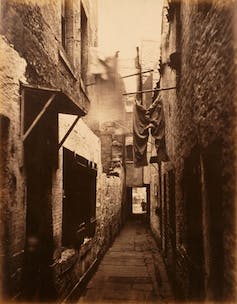

Saltmarket, 1866: working-class dwelling circumstances in Glasgow have been thought of the worst within the UK.

Thomas Annan

These automaton girls nonetheless possessed a glimmer of humanity, as males in energy on the time noticed it: their sexuality. For seamstresses, this was expressed by the perpetual motion of the legs and foot on the pedal. Doctors thought this use of the pedal may induce hysteria and pleasure in girls. The French deputy Charles Benoist wrote in 1904 that mixing women and men within the mills of France and Britain, mixed with the shortage of privateness, the warmth of the coal-fired boilers and the ambient humidity, would exacerbate passions.

The scientific group on the time believed girls lacked the creativeness wanted for duties that have been artistic or that required a excessive degree of end. Women have been thus compelled into unskilled jobs with little accountability, and their entry to coaching was restricted. To guarantee self-discipline – and to guard males from temptation – manufacturing unit homeowners carried out a strict division of duties in keeping with gender and put feminine staff beneath shut supervision. They weren’t, beneath any circumstances, to be distracted from their work.

The homeowners and operators of mills thus sought to manage girls in each manner – not simply bodily and professionally, but additionally morally.

The battle for girls’s rights

Women’s rights chief Anna Munro in Glasgow, circa 1909.

Women’s Freedom League, CC BY

Glasgow’s textile trade started to say no with the outbreak of the American Civil War (1861-65). The United States was the only real provider of cotton to town’s textile industries, and the battle led to a breakdown in commerce and bankrupted many corporations.

As the commercial context turned tougher, working circumstances for girls worsened. The office was aggressive, with job insecurity and monetary pressure. Because males continued to monopolise expert positions and dominate the administration construction, when sexual assaults occurred, girls have been typically reluctant to testify for concern of being dismissed.

Victorian society didn’t recognise sexual harassment, and male integrity was assumed and guarded. If girls did communicate out, their aggressors have been most frequently left unpunished and the fault assigned to feminine employee and her inherently provocative nature. After all, if such acts occurred within the office, how may they actually be sexual harassment?

But as early because the 1860s, girls staff in Glasgow’s factories started to combat again. The decline of the textile trade exacerbated unemployment and financial issue, and working-class girls joined forces with middle-class feminists in demanding gender equality at work. In 1883, the Co-operative Women’s Guild was established, adopted by the Glasgow and West of Scotland Association for Women’s Suffrage (GWSAWS) in 1902. Together, these and different organisations pushed for better protections for girls all through society.

After 16 years of battle, in 1918, girls in Scotland and the remainder of the United Kingdom have been lastly granted the precise to vote. These pioneering organisations and the ladies who based them performed a key position in altering perceptions of girls. From the reclusive, demonised employee to the sturdy, unbiased pressure, with full and equal rights.

![]()

Fanette Pradon is a doctoral scholar on the LLSH doctoral college of the University of Grenoble and the ILCEA4 laboratory.