"Medieval soccer" remains to be performed yearly on Shrove Tuesday in some elements of the UK. Shutterstock/Alamy

Pancake Day, or Shrove Tuesday is as soon as once more upon us. Celebrated in lots of nations world wide, for Christians, Shrove Tuesday marks the final day, or the feast day earlier than Lent – the 40 days main as much as Easter.

This is historically a time of abstinence related to clearing your cabinets of issues like eggs, sugar and fat. Pancakes are eaten on today to make use of up these meals earlier than the fasting season of Lent begins.

But Shrove Tuesday isn’t nearly pancakes. Indeed, traditionally within the UK, it shaped a part of a extra elaborate pre-Lent pageant referred to as Shrovetide, which was all about feasting and sports activities.

Shrovetide video games ranged from merciless animal blood sports activities like cock-fighting to tug-o-wars and skipping. Yet no Shrovetide sport was extra widespread and longstanding than soccer.

Read extra:

The science behind making an ideal pancake

The Village Ba’ Game by Alexander Carse, 1818: a village soccer match in Jedburgh, Scotland.

Painting of a giant group of males taking part in soccer in entrance of a giant rural constructing.

According to gamers from Duns, a city within the Scottish Borders, in 1686, it was “an historic customized all through all this kingdom to play at soccer upon Fastens Eve (Shrove Tuesday)”.

Shrovetide ball video games are documented from the twelfth century onwards, in scores of communities all through Britain and northern France – a number of of which in England and Scotland nonetheless play it right this moment. Shop home windows are boarded up and companies are closed for the day as complete cities take to the streets to hitch within the annual Shrovetide soccer sport.

Shrove soccer

As ancestors to our fashionable video games, people soccer matches assorted significantly within the method of play. But typically, gamers contested a ball with hand and foot, often in direction of a aim.

Shrovetide video games have been usually the massive matches of the day, that includes typically lots of of members. Whether city versus nation, or married in opposition to bachelors, groups battled to maneuver the ball via streets and countryside, in direction of targets like mills, streams and even the church.

Due to its damaging potential, soccer usually fell foul of authority and was banned outright. Medieval royal prohibitions referred to as it “useless, unthrifty and idle”, whereas Puritans deemed it “a bloody and murdering practise”. But others in energy clearly noticed its enchantment, to evaluate from its festive sponsorship in lots of cities and cities.

In Chester, for instance, each Shrove Tuesday within the early Sixteenth century, the Merchant Drapers’ Company obtained a soccer from the Shoemakers’ Company, a wood ball from the Saddlers’ Company and a small silk ball from every man from town married inside the final yr. Under the mayor’s supervision, the Drapers tossed up the balls (which doubled as prizes) for the craftsmen and crowd to play from the frequent area to town’s Common Hall.

Chester’s Shrovetide sponsorship was mirrored all through the British Isles. Craftsmen and guilds performed key roles as members and suppliers of the ball(s). On Shrove Tuesday 1373, for instance, skinners (who pores and skin animals) and tailors performed within the streets of London. Butchers did the identical in Jedburgh, Scotland.

While within the late 18th century out there city of Alnwick in Northumberland, England, the Skinners’ and Shoemakers’ corporations paraded the ball to the match between married and bachelor males. Indeed, leather-based staff like shoemakers have been particularly necessary, crafting Shrovetide footballs in Fifteenth-century London, Sixteenth-century Glasgow and Seventeenth-century Carlisle.

An historic customized

Newlyweds additionally fronted the ball in lots of communities. In Dublin, lately married males needed to current a ball to metropolis magistrates each Shrove Tuesday through the Fifteenth and Sixteenth centuries. Newlywed members of commerce guilds in Perth in central Scotland, and Corfe Castle in Dorset additionally paid a Shrovetide “soccer due”, whereas an identical customized appears to have existed in medieval London.

These have been a part of a broader people custom, the place newly married {couples} owed a “bride ball” or “ball cash” to their group. Since weddings have been customary throughout Shrovetide (and prohibited in Lent), it was a perfect time to gather this cash. Local governments would collect the “wedding ceremony ball” dues, rent drummers and pipers to pump up the crowds, or pay for the footballs straight.

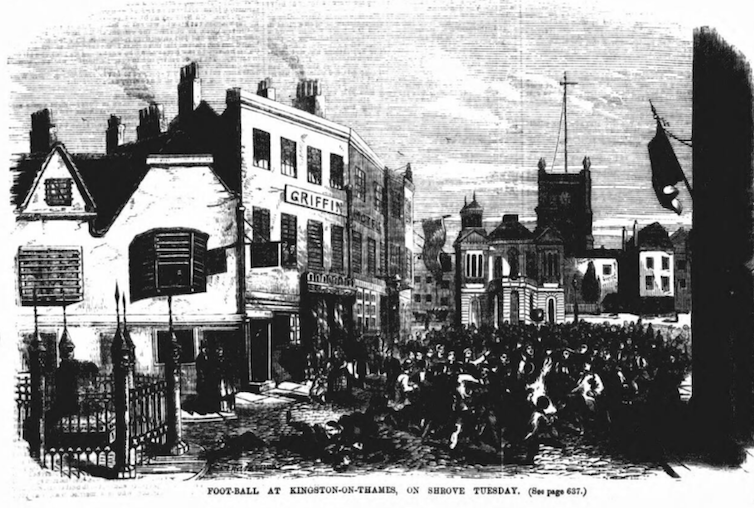

Illustration of Shrove Tuesday soccer in Kingston Upon Thames (1865).

Penny Illustrated Weekly News (London), p. 636, 1865-03-18

Failure to pay your soccer dues might end in imprisonment, heavy fines or the compelled closing of a craftsman’s store. These harsh penalties replicate the value of Shrove Tuesday soccer to those communities. To them, it was not a “useless and idle” sport, however an “historic and laudable customized” of “goodly feats and train” the place participation was usually compulsory.

Officials thus sponsored video games that have been technically unlawful as a result of Shrovetide soccer equated with the “frequent wealth of town”. Participation and patronage of the sport strengthened the standing and privilege that got here with civic membership.

Gradually, authorities in most main cities did withdraw their assist from Shrovetide soccer. Some cities like St Andrews in Scotland merely banned it due to the “many ills” and “dysfunction”.

Others “reformed” the video games into much less harmful entertainments, like foot and horse races in 1540s Chester, or a fire-engine show in 1725 in Carlisle. By the center of the 18th century, formally sanctioned Shrovetide ball video games have been largely confined to smaller market cities and villages, which is the place some reside on to today.

So as you attain for the batter this Shrove Tuesday, keep in mind the historical past of the riotous sport we name soccer and its lesser-known origins as a prelude to pancakes.

![]()

Taylor Aucoin at present receives funding from the British Academy for the Promotion of Historical, Philosophical and Philological Studies. His PhD analysis was partially funded by grants from the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Royal Historical Society, Society for Renaissance Studies, Richard III Society, Sidney Perry Foundation, the Humanitarian Trust, the Bristol Graduate Research Centre, Bristol Alumni Foundation, Sir John Plumb Trust, Sir Richard Stapley Trust, Folklore Society, Society for Theatre Research, and the Medieval Academy of America.