A nineteenth century picture of Parihaka, New Zealand, with Mount Taranaki within the background. Getty Images

The day my great-grandfather Andrew Gilhooly was buried at Taranaki’s Ōkato cemetery in early February 1922, Jas Higgins performed the Last Post. Neither man had seen energetic service within the “nice warfare” with which that ritual is most carefully related. Rather, each had served within the New Zealand wars, an earlier collection of conflicts fought throughout the mid-to-late nineteenth century as a part of the colonisation of Aotearoa New Zealand.

In New Zealand and Australia it’s a mark of honour to have ancestors who fought on the Dardanelles or on the Somme or Passchendaele. A nationwide origin fantasy has been constructed across the Anzacs, replete with a day of remembrance, outsized monuments, and a wealthy custom of rituals which can be rehearsed yearly “lest we neglect”.

Nothing like the identical emotional (or monetary) funding is made in remembering the wars that came about at residence. Our personal colonial violence, in Taranaki and at Ōrākau, Pukehinahina/Gate Pā and elsewhere, has been relegated to the margins of the nationwide consciousness. It’s an ongoing means of selective historic amnesia that we’re solely slowly starting to handle – not a lot lest we neglect, as greatest we neglect.

This would possibly clarify why I grew up realizing subsequent to nothing about my maternal great-grandfather. Yes, there have been loads of tales about his spouse (roundly condemned as having been a “tough” girl) and 6 youngsters (farmers, priestly prodigies and musical spinsters). However, aside from the naked information that he was born right into a poor farming household in County Limerick in Ireland and had served within the New Zealand Armed Constabulary (AC), about Andrew there was solely silence.

Last 12 months I wrote a small household memoir, The Forgotten Coast, in an try to handle that and different silences in my household. As it turned out, the bugling of Jas Higgins on the graveside was the least of the issues I didn’t learn about my great-grandfather.

Family silences

Andrew turned the conundrum on the coronary heart of the e-book, however he was not the explanation I started it. On Christmas Eve 2012, my father died throughout coronary heart surgical procedure we thought can be routine, however which quickly turned difficult. There have been issues I want I’d stated to him, and I began writing as a approach of doing so.

(Mind you, Dad wasn’t a lot given to speaking both. After he died, simply earlier than his funeral, we have been in a position to have him at residence with us – and greater than as soon as, as we ate, drank and reminisced about him, somebody noticed that his verbal contribution was not noticeably lower than it might have been had he nonetheless been alive.)

As the e-book unfolded, different folks and different issues started to intrude. It turned more and more clear that if I used to be to make sense of the silences there had typically been between me and Dad, I might additionally want to handle these which draped round different relationships, together with some inside my mom’s household.

À lire aussi :

From Parihaka to He Puapua: it’s time Pākehā New Zealanders confronted their private connections to the previous

Dad was raised in an orphanage, however married into a big, sprawling household that was – by advantage of three farms, which Andrew and his spouse Kate got here to manage – a part of a coastal Taranaki group with a powerful sense of id. Both the folks and the place, within the west of New Zealand’s North Island, have been vital backdrops to my dad and mom’ life collectively. So I couldn’t actually sort out Dad with out additionally coping with the origins of that context.

The downside was that no person appeared to know a lot about Andrew: there was nothing in Mum’s household’s collective reminiscence about the place he was born, when he got here to Aotearoa, or about his involvement in each the navy and agricultural campaigns of dispossession in Taranaki. Nothing aside from silence, that’s.

So I set about filling within the gaps, probably the most consequential of which involved the half Andrew performed within the occasions via which Taranaki Māori have been alienated from their land. And the extra I realized about that, the clearer it turned to me that my circle of relatives’s origin story right here in Aotearoa can be rooted in historic amnesia.

One of the results of that is to obscure the uncomfortable paradox that my ancestor, whose personal folks had been dispossessed by English colonisers, had participated in and benefited from the confiscation of one other folks’s land.

The Irish mannequin

There are two elements to this contradiction. The first is that for 9 years Andrew Gilhooly served within the AC, a hybrid police-military drive designed to subjugate Māori, and explicitly modelled on an Irish organisation that had managed his personal folks via violence.

The institution of the AC in 1867 mirrored the colonial administration’s need for a drive modelled on the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), which was “typically acknowledged [to be] the best drive on the earth”. Indeed, New Zealand’s model of the RIC was arrange within the very 12 months by which the Irish Constabulary took on the “Royal” moniker, following its function within the suppression of the Fenian Rising.

True, it was removed from uncommon for Irish Catholics like Andrew to serve in both drive. In the 1870s, greater than 75% of the RIC’s constables have been Catholic (though Protestants accounted for 80% of the officer class), whereas 37 of the 167 males who joined the AC within the 12 months Andrew signed up (1877) have been additionally Irish-born Roman Catholics.

But the purpose is that in 1867, New Zealand’s colonial administration copied the template of an establishment developed to pacify the Irish and let it free on one other indigenous inhabitants.

A decade later a type of Irish indigenes – my great-grandfather – joined that drive. And 4 years after that, he was standing alongside 1,588 different navy males ready to begin the invasion of Parihaka pā, residence to the good Māori pacifist leaders Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi.

Armed constabulary awaiting orders to advance on Parihaka pā, 1881.

Alexander Turnbull Library, CC BY-NC-ND

Living on confiscated land

The second facet of the paradox flows from Andrew’s subsequent function within the agricultural marketing campaign that accomplished the alienation of Māori land in Taranaki. Shortly after his navy service resulted in 1891, he returned to the province the place, in time, he and his spouse Kate would come to manage three farms that have been a part of the 1,275,000 acres confiscated from Māori by the colonial state in 1865, and subsequently granted or bought to settler farmers and their households.

As with the institution of the AC, so too the laws underpinning the confiscations had Irish antecedents. The two principal statutes have been the Suppression of Rebellion Act and the New Zealand Settlement Acts of 1863.

À lire aussi :

How NZ’s colonial authorities misused legal guidelines to crush non-violent dissent at Parihaka

The former, which was nearly copied from the 1799 Irish legislation of the identical identify, suspended the correct of trial specifically circumstances in order to “punish sure aboriginal tribes of the colony”. Through the second, which was based mostly on Cromwell’s Act of Settlement in 1652, the colonial state gave itself permission to confiscate Māori land for “public functions”.

For generations, Andrew’s personal folks had farmed leasehold land within the township of Ballynagreanagh, land that had handed out of Irish possession centuries earlier than he was born in 1855. Andrew left behind the “at will” contract (which permitted land house owners to evict tenants with out purpose), the absentee English landlord and the small household plot when he stop Ireland in 1874.

But the irony is that the trail he took out of poverty was the identical one down which his forebears had been marched into penury.

Big and small histories

The devices used to displace the querulous Irish – the statutory creation of “rebels”, the parliamentary confiscation of land, the institution of a police-military drive, the administration of inequitable and iniquitous leases – are the identical as these subsequently deployed to take care of the troublesome Māori. The distinction was that when Māori have been on the receiving finish, Andrew turned the beneficiary of injustice.

Andrew Gilhooly got here from poor Irish farming folks, who leased a slip of land within the parish of Kilteely from an English landlord who lived in Devon. In the area of a single era, he and his spouse would reinvent themselves socially, economically and politically, laying declare to acreage 16 occasions the dimensions of that tiny plot in Limerick.

Those new New Zealand acres enabled my great-grandparents to solid off the yoke of Irish poverty and to turn into revered members of the Taranaki coastal farming group. By the time Jas Higgins performed the Last Post for Andrew in 1923, the Irish farm labourer had lengthy since made approach for the Taranaki settler-farmer, which was an altogether higher factor to be.

À lire aussi :

Learning to dwell with the ‘messy, difficult historical past’ of how Aotearoa New Zealand was colonised

Because this transformation was enabled by legal guidelines and establishments based mostly on these which had impoverished his personal ancestors, it’s simple to border Andrew because the colonised turned coloniser. Certainly that was the unequivocal place I’d reached by the point The Forgotten Coast was printed.

But because the e-book has made its approach on the earth, and different Pākehā have contacted me with typically intimate reflections on their very own histories with colonisation, I discover that place shifting. An unequivocal view will all the time provide certainty and readability, however typically on the expense of feeling just a little compelled.

Perhaps, I now surprise, it’s unfair to infer an intent from the sweeping, systemic forces of historical past and impute it to a specific particular person, as if there is no such thing as a distinction to be drawn between the “massive story” of colonisation and the “small tales” of individuals like my great-grandfather.

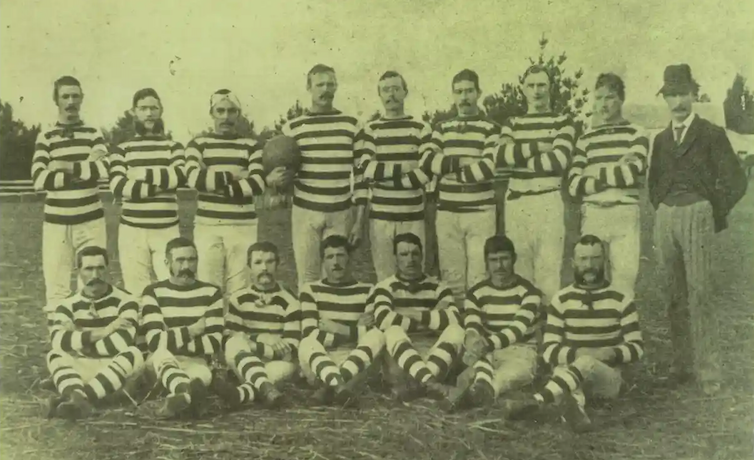

Becoming a New Zealander: Andrew Gilhooly (holding ball) with the AC rugby crew in 1881.

Author supplied

Becoming Pākehā

Whatever his private culpability, the e-book has additionally modified my understanding of time. New Zealand historian Charlotte McDonald rightly questions the usual view of the previous as a set of “actions and speech acts with no pulse, drained of any capability to have an effect on the current”.

Rather, the three Gilhooly farms generated materials and immaterial advantages that proceed to form the lives of Andrew’s descendants. They are a type of dwelling inheritance – and they’re, after all, not accessible to these from whom the land was confiscated.

One of the intangible positive factors is the clear sense I’ve of being of and from this place referred to as Aotearoa. I consider myself as Pākehā (a New Zealander with European ancestry) simply as of late – however I additionally surprise when Andrew stopped being Irish and turn into this new factor, a New Zealander. At what level, if ever, did he cross his private Rubicon?

À lire aussi :

Putting Aotearoa on the map: New Zealand has modified its identify earlier than, why not once more?

I’ve no approach of realizing, and neither can I apprehend what might need been misplaced in that course of. Andrew has and can all the time have work to do as one among Alan Bennett’s “biddable useless”, his job without end being to depart the tragedy of Ireland for the sunlit uplands of a brand new world. But I think about that this course of was not uncomplicated for him or for different migrants; that alongside the social and financial metamorphoses there have been additionally splinters of exile and rupture.

Nonetheless, there was a technique to the forgetting that has taken place in my household; a purpose the ghost tales of the Armed Constabulary and the farming of confiscated land went untold for thus lengthy. My model of the historic amnesia that applies extra broadly to the New Zealand wars has allowed me to keep away from (till now) the uncomfortable paradox I’ve walked you thru right here.

It has meant I’ve been in a position to fortunately declare my place within the pioneer-settler basis fantasy, the one which all the time begins with the acquisition of the household farm and ignores the stuff that got here earlier than (till now). As the forgetting ends, issues should change.

![]()

Richard Shaw ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de elements, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer revenue de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.